This past Tuesday, I was on the panel for a program sponsored by our local Maimonides and Cardozo Societies – made up of Jewish physicians and lawyers, respectively. I was the “Jewish Expert” on the panel. The subject was based on a book written a few years ago called Larry’s Kidney: Being the True Story of How I Found Myself in China with My Black Sheep Cousin and His Mail-Order Bride, Skirting the Law to Get Him a Transplant–and Save His Life, by Daniel Asa Rose. The author spoke for the first half of the program, so I was only able to touch the surface of the topic from a Jewish perspective. It is a vitally important topic of life-and-death, and there are many misconceptions, so I would like to spend time this morning going into more depth.

In the United States, an average of 79 people receive an organ transplant every day. Sounds good, right? Also, on average, 22 people die every day waiting for a transplant. That is more than 8,000 people per year whose lives could have potentially been saved if more organs had been available. If more people in this country were registered organ donors, many more lives could be saved.

There are numerous complicated issues, both ethical and medical, when it comes to organ donation. Let me try to summarize a few of them.

We can divide organ donation into four categories. The first is live organ donations for which there is minimal risk to the donor. Examples include blood, bone marrow, skin, and even kidney donations. The second category is live organ donations for which there is risk to the donor. Examples include liver lobe and lung lobe donations. The third category is cadaver donations in which the organs can be harvested after the donor’s heart stops beating. An example is a cornea. The final category is a cadaver donation for which the cardiovascular system has to be kept working by artificial means until shortly before the organs are removed. This is the case for heart, lung, and pancreas donations.

For each of these categories, the ethical and medical considerations are different. How much risk is tolerable? What is the definition of death? At what point after the withdrawal of life support can organs be harvested? What factors should be considered when determining which of multiple candidates should receive an organ? Can live donors be paid for their donations? Each of these questions is extremely complicated. There is a vast body of writing from the perspective of medical and religious ethics that deals with every one of these issues.

Until fairly recently, Israel had an organ donation rate that was far below other developed countries. Because there were so few Israelis willing to donate their own or their loved ones’ organs, “transplant tourism” became very popular. Organ brokers would advertise their services on the radio and in newspapers. Not only were there not any laws prohibiting Israelis from going abroad for organ transplants, but the national health insurance would even reimburse patients for their expenses. So Israelis would travel to China, Brazil, and other countries to receive life-saving organ transplants.

Is there anything wrong with this?

The problem is that in many countries, there is little regulation and no transparency. China, for example, has become a major center for organ transplants over the past twenty years, advertising their services to wealthy patients around the world. Where do the organs come from? China does not maintain a national organ donor database – so nobody really knows.

Over the years, there have been numerous allegations and investigations claiming that Chinese prisoners are being executed for their organs – and not just those imprisoned for violent crimes. Also included are political prisoners, as well as tens of thousands of member of the Falun Gong religious sect. With the vast amounts of money to be made, and the lack of oversight and transparency, it is no wonder that Chinese politicians, judges, and medical workers up and down the system allow this to happen.

From the perspective of Judaism, this is absolutely wrong and immoral. While I do not have to sacrifice myself to save another person, and I am permitted to protect myself if I am being attacked, under no circumstances can I kill another person to save my own life.

Which is why it is such a chilul hashem – a desecration of God’s name – that there have been numerous cases of Jews convicted for organ trafficking, in Israel and in the United States. One of the factors contributing to this embarrassment is the low organ donor rate in Israel.

Why are so few Israelis willing to be organ donors?

There are several assumptions that people make about Jewish law. First of all, we know that the body is considered to be sacred in Judaism. When a person passes away, we treat the body with the utmost respect, cleaning and dressing it quickly, and returning it to the ground from which it came. Autopsies are generally prohibited, as well as embalming. The proper care of a body before burial is considered to be one of the greatest mitzvot that we can perform.

The removal of organs before burial, therefore, would seem to be a violation of Jewish law and custom. Another complicating factor is the traditional belief in a future resurrection in the days of the Messiah. If a person is buried without all of his or her organs, will he or she be resurrected whole in body?

Because of these beliefs, many Jews have been reluctant to register themselves or agree to donate their loved ones’ organs. That is why the organ donor rates are so low in Israel.

But there is a competing principle which most halakhic authorities across denominations consider to be even more significant. Pikuach nefesh, the saving of a life, is such an important value that it trumps even the special sanctity of the body.

The Torah states, lo ta’amod al dam re’echa. Do not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor. This means that if we have the ability to save the life of another person, we have an obligation to do so. Halakhic codes stretch this concept to require us to spend our money, or even endure personal discomfort, to save the life of another person.

While organ donation was not a possibility at the time these laws developed, the principle is relevant. So rather than ask “are Jews permitted to donate their organs?” the question really ought to be “Are there ever circumstances in which a Jew is not required to donate his or her organs?”

While some modern poskim, including Orthodox ones, today use the term mitzvah to refer to organ donation, it seems clear that they mean it not as an obligation, but rather as a midat chasidut, a particular pious act that is lifnim mishurat hadin – beyond the strict letter of the law.

So what can be done to increase organ donor rates and save more lives?

In the United States, we have an opt-in system. Most states, including California, have recruited the DMV to register donors. If you have a license you are probably familiar with this. When you go to get your license, the DMV clerk asks you if you want to be an organ donor. To be registered, you have to say yes. An opt-out system automatically assumes that everyone is an organ donor except for those who explicitly state that they do not want to be. Some countries have been successful with this.

While an opt-out system might seem to many Americans like a gross invasion of personal autonomy, it is defensible and maybe even preferable from a Jewish perspective.

In Judaism, there is a concept that I can perform an act or make a decision on behalf of another person without his or her knowledge, and potentially even against his or her will, if it causes that person benefit. Some authorities apply that concept to organ donation. Let’s say that my loved one is in a coma and is determined by doctors to be brain dead. When I agree to donate the organs, my loved one gains the benefit of saving a life.

So a Jewish argument could definitely be made in favor of an opt-out organ donor system.

Another possibility is the solution that Israel enacted in 2008. It made it illegal to travel abroad for an organ transplant, or to engage in organ trafficking. It defined death as “brain death,” clarifying the circumstances under which cadaver donations can take place. And it created an incentive system to encourage more donors. Donors now receive reimbursement for all medical expenses related to the donation, as well as for lost work. Live donors also receive preference if at some later time they find themselves in need of an organ. In addition, if two people on a transplant waiting list are at the same tier of eligibility, the one who has been a registered organ donor will receive preference. Finally, the immediate family members of a deceased person whose organs were donated will also receive preference.

The law is controversial, as it introduces non-medical factors for determining eligibility. But it has caused organ donor rates to increase in Israel.

This morning’s Torah portion, parashat Terumah, offers us a fitting model for how we might understand organ donation. In the opening statment, God instructs Moses:

דַּבֵּר אֶל־בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וְיִקְחוּ־לִי תְּרוּמָה מֵאֵת כָּל־אִישׁ אֲשֶׁר יִדְּבֶנּוּ לִבּוֹ תִּקְחוּ אֶת־תְּרוּמָתִי.

Tell the Israelite people to bring Me gifts; you shall accept gifts for Me from every person whose heart so moves him. (Exodus 25:2)

The Hebrew word for donation is terumah. The Israelites are being instructed to bring their donations for the construction of the mishkan, the Tabernacle. Rashi asks, why does God specify v’yikchu li terumah. “Take for me a donation?” After all, God certainly does not have any physical needs. Rashi answers with the word lishmi – for my sake. In other words, these are to be purely selfless, altruistic donations. There should be no personal motive.

But a passage in the Talmud states the opposite: “If a person declares ‘this coin is for tzedakah so that my child should live, or so that I can earn a place in the world to come’ – such a person is a tzadik gamur – a totally righteous individual.” (BT Rosh Hashanah 4a) Commenting on this, Rashi explains im ragil b’kach – if the person is in the habit of giving tzedakah regularly.

So which is it, Rashi? Are we supposed to give altruistically, without hope of personal benefit, or is a donor just as righteous if or she receives some advantage?

Is it the American system, which relies solely on altruistic donations, or the new Israeli system, which seeks to create positive incentives that cannot be harmfully manipulated?

Maybe the point is that it doesn’t matter. Whatever the motivation, the end result of more organ donors is that more lives will be saved. So if you are not already a registered organ donor, get on the list. If, God forbid, we should ever find ourselves in the situation of having to make a decision about our own or a love one’s organs, let us please remember that Judaism has something to say about it.

And in so doing, in making the ultimate gift of saving the life of a human being made in God’s image, the terumah can surely be said to be lishmi, for God’s sake.

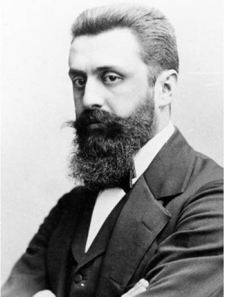

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.