If you ask most Jewish kids in America what their favorite holiday is, they’ll say Chanukah. From a religious standpoint, it is not really that important of a holiday. In Israel, Chanukah is really not that big of a deal, certainly when compared to the other Jewish holidays. It got to be this way here in America because of its proximity to a certain other non-Jewish holiday. “The Jewish Christmas” and all that.

At least, that is the typical complaint made by Rabbis lamenting the over-commercialization of Chanukah.

But maybe this is not such a uniquely American experience.

I came across a story written over one hundred years ago at a transitional moment in Jewish history. A story that is as relevant today as it was then.

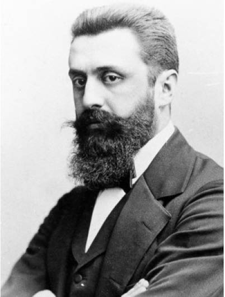

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.

I was just lighting the Christmas tree for my children when Gudemann arrived. He seemed upset by the “Christian” custom. Well, I will not let myself be pressured! But I don’t mind if they call it the Hannukah tree–or the winter solstice.

Two years later, Herzl is living in Paris and reporting on the Dreyfus Affair. The rampant antisemitism shakes him to his core and leads him to abandon his earlier assimilationist positions. Herzl concludes that the only solution for the Jewish people is to have a homeland of their own, along with a re-embracing of Judaism. With this realization, Herzl convenes the First Zionist Congress, and modern Zionism is born.

In December 1897, Herzl writes a short story entitled “The Menorah” which appears in the journal Die Welt, a weekly newspaper that he has recently begun publishing to promote Zionism. The following is a paraphrased summary of Herzl’s story, utilizing some of his language. (The full text of the story can be read here.)

Deep in his soul, he began to feel the need to be a Jew. His circumstances were not unsatisfactory; he enjoyed ample income and a profession that permitted him to do whatever his heart desired. For he was an artist.

Of course, Herzl is writing about himself. He goes on to describe a thoroughly assimilated European Jew of the late nineteenth century. When antisemitism rears its head, this enlightened Jew assumes that it will fade just as quickly. But it does not, and his soul begins to wear down.

He begins to think of his Judaism. Despite its alienness, he begins to love it intensely. Gradually, his yearning crystalizes into a conviction that he must return to Judaism. His closest friends think he is crazy, ridiculing him behind his back and even laughing in his face. But he is indifferent to their sneers.

As an artist of the modern school and a man of the senses, he has embraced many non-Jewish habits and ideas. How can he reconcile this modernity with his return to Judaism? Doubt plagues him. Perhaps it is too late for his generation, which has become so heavily influenced by alien cultures. But the next generation, if it is trained in the proper path, will be able to make the return.

Until then, the artist has allowed the holiday of the Maccabees to pass by unobserved. Now, however, he makes this holiday an opportunity to prepare something beautiful which should be forever commemorated in the minds of his children.

… He buys a Menorah, and when he holds the nine-branched candlestick in his hands for the first time, a strange mood overcomes him. He grows nostalgic and sad when he recalls the memory of burning lights in his father’s house.

But the tradition is neither cold nor dead, he realizes. It has passed through the ages, one light kindling another.

The artist begins to think about where the shape of the Menorah came from. He sees in it the form of a tree: branches emerging from a central trunk to the right and the left, all ending at the same height. Then the ninth branch projects to the front to play the role of shamash, servant to the others.

What mysterious meanings have previous generations passed down to the next about this simple, natural shape. He imagines that he might be able to water this withered tree and restore it to life. He joyfully recites its name to his children – Menorah – and delights in hearing it repeated back to him out of their mouths.

He lights the candle on the first night and tells his children what little he knows about the origin of the holiday. The wonderful incident of the lights that strangely remained burning so long, the story of the return from the Babylonian exile, the second Temple, the Maccabees – our friend tells his children all that he knows. It is not very much, to be sure, but it serves.

The next night, with the second candle, the artist’s children repeat back to him the stories that he had told them the night before. Even though the stories are the same, they seem to him to be new and beautiful.

Each subsequent night is brighter than the previous. The artist muses on the little candles with his children until the profundity becomes too deep for him to share.

When he first resolved to return to his people, he thought simply that he was doing an honorable and rational thing. He never dreamed that he would find something that satisfied his yearning for beauty. Yet that is what he found.

After the holiday, he sketches out a plan for a new Menorah to present to his children the following year. The artist is searching for living beauty, so he does not limit himself to the strict traditional form of the Menorah. Yet his design still takes form as a tree with slender branches.

The following year, he lights the Menorah with his children, the light increasing. On the eighth night, a great splendor streams from the Menorah. The children’s eyes glisten. For our friend, all this is the symbol of the kindling of a nation. When there is but one light, all is still dark, and the solitary light looks melancholy. Soon, it finds one companion, then another, and another. The darkness must retreat.

The light comes first to the young and the poor – then others join them who love Justice, Truth, Liberty, Progress, Humanity, and Beauty.

When all the candles burn, then we must all stand and rejoice over the achievements. And no office can be more blessed than that of a Servant – a shamash – of the Light.

What a change! In just two years, Herzl is transformed from a father casually lighting up a Christmas tree for his children to a Jew finding profound beauty and meaning in the kindling of the Menorah. Such a tremendous inspiration. What a legacy he has left us!

Chag Urim Sameach. Happy Festival of Lights.