Jacob the Liar. Jacob the Trickster. Jacob our Patriarch.

Every year, when we come to this week’s Torah portion, at least one person, usually more, comes to me with something critical to say about Jacob. How can such an immoral person, a thief and manipulator – be one of our Patriarchs? But the Torah tells the story from a bird’s eye view, without passing judgment on Jacob or any of the other characters in the story. What about Jacob the person – the son, the brother? How did he become who he became? With your permission, I will attempt to delve into Jacob’s character from a first-person vantage point.

My name is Ya-akov, which means “Heel.” Why anyone would name their child after a heel is beyond me. They say that I came out of my mother second, holding on to my twin brother’s foot as if I didn’t want to be left behind, or perhaps even as if I was struggling to come out first. Anyways, being called a “Heel” all of the time has got to be somebody’s idea of a cruel joke.

Right now, I’m on the run. My brother vowed to kill me – and I believe he just might do it. So I had to skip town in a hurry, with nothing but the clothes on my back.

Let me tell you about my brother, Esau. First of all, I cannot believe that we are even related, much less twins. He is my opposite in every way. He is big and strong. He has red hair all over his body. He spends as much time as he can away from home, hunting out in the fields with his bow and arrow.

And let’s just say that he is not much of a reader. He is brash, quick-tempered, and prone to hyperbole – not that he knows the meaning of the word.

Not only that, I think Esau might be evil. What does he do all day when he is out in the fields? I know he is a good hunter, and he always brings home a fresh kill for my father, but he is gone so long that he has to be up to other things.

I have my suspicions. And there are rumors. They say (Genesis Rabbah 63:12) he spends a lot of time with the ladies. And not just the single ones. (Ibid. 65:1) I even heard that he once forced himself on a young woman who was engaged to be married. But nobody is going to mess with Esau – so he gets away with it.

I also overheard our servants whispering that they heard Esau killed a man. There weren’t any details, but knowing my brother, it wouldn’t surprise me one bit to find out that it is true.

And yet, my father, Isaac, clearly favors Esau. He barely even acknowledges me. Every day, Esau struts back into our homestead with his bloody carcass from that day’s hunt. He roasts it up just how dad likes it. Then he changes out of his soiled clothes (Deuteronomy Rabbah 1:15) and brings the meat to father with a glass of wine (Genesis Rabbah 63:10), which he keeps refilling. He plays the part of the obedient, respectful son to a T.

He asks father questions to try to foster an aura of righteousness that couldn’t be farther from the truth. One day, I overhead him asking about the proper way to tithe salt and straw, as if he has ever tithed anything or offered a single word of praise to God in his life. But father thought Esau was so pious, he talked about it for days. There isn’t even an obligation to tithe salt or straw. (Rashi on Genesis 25:27) He hunts our father’s emotions just like the prey that he tracks out in the wilds.

The worst part of it all is that this so-called brother of mine, simply because he came out a few seconds before me, is entitled to receive a double inheritance of our father’s estate. This brute, who knows nothing about running a farm, managing a household, or maintaining good relations with neighbors, will get to take over the family business. He is going to squander everything that our grandfather Abraham and our father Isaac built to satisfy his own gluttonous passions.

Does my father, Isaac, see any of this? He is a wise man, and a good man. How can he be so blind?

I sometimes think that he feels guilty about what happened to his own half-brother, Ishmael. Even though Uncle Ishmael was the son of a slave, he was still Grandfather Abraham’s oldest child. After my father was born, Ishmael was sent away so that we wouldn’t be a threat, and so that father could be the uncontested heir. Ishmael grew up into a wild man, quite the opposite of dad. But I wonder if father feels that he somehow owes something to Ishmael that he cannot repay, and so he overlooks Esau’s terrible qualities.

I could not let Esau inherit our father’s possessions. Not because I thought they should be mine. But because Father doesn’t see Esau as he truly is. So when opportunity presented itself, I took advantage.

One afternoon, I was cooking a red lentil stew. I have to stay, I am quite the chef. Because I have spent so much of my time around the tents and with mother, I have picked up a thing or two in the kitchen.

Esau came in from the field in one of his moods. He had been tracking an ibex or antelope or something that had gotten away, so he was pretty upset.

“Argggh!” was the announcement of his approach. I heard the clattering sound of a bow and quiver of arrows as it was thrown to the ground.

Then Esau shoved his ugly, dirty, hairy face in front of mine. “I’m starving!” he shouted. “Give me that red red stuff!”

Startled, I looked in his face, and saw my chance. “Sell me your birthright, and you can have as much as you want.” I knew exactly how he would respond.

“I’m dying of hunger here. I’ve got no use for a birthright!”

But I wanted to be sure. “No. You’ve got to swear to me.”

“Fine! Whatever! I swear you can have the birthright. Now gimme that red stuff!”

So I let him have it. He ate, drank, got up, and stormed off. I don’t think he even tasted the soup.

Now let me tell you about my father. One year, there was a famine, so he moved the household to Philistine territory, near Gerar. Father did not feel very confident in himself, so he told everyone that his wife was actually his sister so they would not be tempted to kill him and steal her. Well, the ruse did not last very long. When King Avimelech saw them fooling around out in the fields one day, he summoned father to the palace for an explanation.

Overall, though, we did pretty well in Gerar. Father made a lot of money. But the locals were not pleased, so they started stopping up all of his wells. Those wells, by the way, were wells that Grandfather Avraham had dug many years ago. Then the King ordered us to leave. Instead of standing up for himself, father just acquiesced, and we moved further out, to a dry riverbed.

Farther sent his workers out to re-dig the stopped-up wells. Whenever they struck water, the locals came out to claim them as their own. So what did father do? He gave in and moved on to dig another well. After three times, he just picked up and moved us all far away to Be’er Sheva.

I hate to say this, but my father is not a brave man.

He is blind to my brother’s wickedness, and he lets people push him around.

Mother? She is another story entirely. Rebecca is a force to be reckoned with.

Like I said, I spend most of my days by the tents. But those days are not idly spent. She makes sure of that. Mother is constantly drilling me to learn. She made sure I could read, and that I knew my numbers. She taught me to watch people, to read their emotions and understand their motivations so that I would know how to deal with them. She made sure that I understood how the household worked, and how to manage our people.

Let me tell you – she is a demanding teacher. Do not talk back to that woman. You do what she says, or else.

Don’t get me wrong. I love my mother. But it’s a complicated relationship. Sometimes I think that she is too much in my business. She misses nothing.

At least she doesn’t have any illusions about her eldest son. Mother knows exactly who, and what, Esau is. Unfortunately, father cannot tolerate anything bad said about him – even when she confronts him with the truth. It’s infuriating.

One day, mother came to me in a rush. “Quick, Jacob. Your father has just asked your brother to go out and hunt him some game. He is about to give him his innermost blessing. We cannot allow that to happen!”

“But,” I protested, “I’ve already gotten the birthright from him. What do I need the blessing for?”

“The Lord made a sacred promise to your grandfather that his descendants would become a great nation and be a blessing to the world. That blessing passed on to your father. It cannot go on to your brother.”

“But he is the oldest.” I said.

Then her face softened. “I never told you this. My pregnancy with you was terrible. I thought I was going to die. It was something unnatural. So I asked the Lord ‘what’s the point of all this?’ and I received an answer: ‘Two nations are in your womb, two separate peoples shall issue from your body; one people shall be mightier than the other, and the older shall serve the younger.'””

“So Jacob, it must be you. Go select two animals from the flock. I’ll prepare them the way that your father likes. Bring them in to him, and he will give you his blessing.”

I sucked in my breath and spoke back to her again: “But mother, there is no way that father is going to think I am Esau. Yes, he is blind, but Esau is covered in hair, and I’m smooth-skinned. As soon as father touches me, he is going to know who it is, and then I’m going to be cursed.”

“Let the curse fall upon me.” she snapped. “Just do it. The future depends on it.”

You should have seen her in that moment. Her eyes were blazing. Her face was scarlet. I had to do what she said.

So I got the animals and gave them to mother. She prepared the meal while I snuck into my brother’s tent to steal his clothes. Then I took some animal skins and put them on my arms so that they would feel like Esau’s. Yes. He is that hairy.

I brought the food in. “Father,” I said. “It’s me your son.”

“Which son are you?” he asked.

I gulped. “I am Esau, your first-born. I did what you told me. Please sit up and eat of this game, so that you can give me your innermost blessing.”

“That was fast,” he said. “How did you come back so quickly.”

Without thinking, I responded, “Because the Lord your God granted me good fortune.” That was a stupid thing to say. Esau would never talk like that.

Father seemed suspicious, and he said, “come closer so I can feel you, and know whether you are Esau or not.” He suspected!

So I approached and nervously held out my arms for him to feel.

“The voice is the voice of Jacob, yet the hands are the hands of Esau. Are you really Esau?”

“I am.”

“Then serve me so that I may eat of my son’s game and give him my innermost blessing.”

So I did. My father ate, and then he called me over close and asked me to kiss him. Holding my breath, I did as he asked.

“Ah, the smell of my son is like the smell of the fields that the Lord has blessed.”

Was this really going to work?

Apparently it was. He blessed me. “May God give you Of the dew of heaven and the fat of the earth, abundance of new grain and wine. Let peoples serve you, and nations bow to you; be master over your brothers, and let your mother’s sons bow to you. Cursed be they who curse you, blessed they who bless you.”

Believe me, I got out of there as fast as I could. I rushed past mother, who was waiting outside the tent, and went to get out of sight as quickly as possible. I did not want to be around when my brother got back.

Good thing, too. Because Esau showed up seconds later. I was hiding in my tent, so I don’t know what happened when they figured out what I had done. But a little while later, I heard the loudest scream I have ever heard. It was filled with pain, anger, and rage.

That night, mother came to my tent. She grabbed a travel bag and started rushing around, grabbing things to pack into it. “Jacob, you have to leave immediately” she said. “Esau is furious. He is swearing that as soon as your father dies, he is going to come after you to kill you. Here is what I want you to do. Leave the country, and travel to Haran, where I was born. Find my brother Laban. You can stay with him for as long as you need. After Esau calms down, I’ll send for you.”

That’s it!? My mother forces me to trick my father and infuriate my brother – and now I’ve got to go into exile!? What did she think was going to happen? Not that I shouldn’t have been the one to get the blessing, mind you. I agree with her there. There is no way that Esau’s descendants will be blessings to the world.

But it’s not like she gave me any alternatives. What was I supposed to do?

So I packed my things, and was about to leave when my father sent for me. “Uh oh. Now I’m in for it,” I thought. “Here comes the curse.”

I went back into father’s tent, terrified of what was to come next.

“You shall not take a wife from among the Canaanite women,” he ordered. “Up, go to Paddan-aram, to the house of Bethuel, your mother’s father, and take a wife there from among the daughters of Laban, your mother’s brother.”

It sounds like mother got to him first. She must have complained to father about the local women so that he would think that it was his idea to send me abroad. She is a devious one.

Then father gave me another blessing. “May El Shaddai bless you, make you fertile and numerous, so that you become an assembly of peoples. May He grant the blessing of Abraham to you and your offspring, that you may possess the land where you are sojourning, which God assigned to Abraham.”

He didn’t say a word about my deceiving him. Nothing. I was flabbergasted, but I wasn’t going to stick around to find out what he was going to say next. I hit the road immediately, and that’s where I am now. Be’er Sheva is behind me. I think I am out of my brother’s range.

So now you know my story. Before you judge me too harshly, please consider what I have had to deal with in my life up until now: a brother who could not be more different, who is crude, uneducated, wicked, and deceitful; a father who cannot stand up for himself, and who allows himself to be deceived; and an overbearing mother who knows how to get what she wants, but whose love is, at times, suffocating.

I think it’s good for me to get away for a while, to escape this atmosphere of dishonesty and duplicity. It’s time for me to chart my own course.

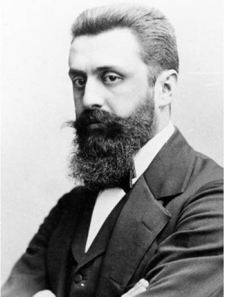

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.