There was a momentous decision in Israel at the beginning of this week. The Israeli Cabinet voted to endorse the Mendelblit Plan to create an official egalitarian section of the kotel, the Western Wall. It legally designated the entire area as a pluralistic space that belongs to the entire Jewish people. For the first time, the government will fund what until now has been referred to as the “Egalitarian Kotel,” or Ezrat Yisrael, and has been maintained by the Masorti, or Conservative, Movement.

Here are some of the details. The existing segregated men and women’s sections will remain in place and continue to be administered by the Charedi Western Wall Heritage Foundation, under the leadership of Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz. The plaza behind those two sections will remain under the administration of Rabbi Rabinowitz, although it will now be officially designated as a public space and used for national and swearing-in ceremonies for the IDF. Whereas in the past, women were prohibited from singing or speaking at those ceremonies, there will no longer be such discrimination.

Previously, violations of “local custom” have been punishable by 6 months in prison or a 500 shekel fine. The Charedi authorities have been able to define “local custom,” which has resulted in many women being arrested for praying over the past two decades. The new plan decriminalizes women’s prayer.

Regarding the Egalitarian Kotel, located in the Davidson Archaeological Garden, which is to the South of what we generally think of as the Western Wall, there will be a number of changes. The space will expand significantly from the current 4800 square feet to nearly 10,000. In comparison, the segregated sections comprise 21,500 square feet. Currently, the entrance is located next to a poorly signed guard booth outside of the main entrance gate to the Kotel plaza. That will change, with a prominent entranceway being built in the main plaza area. There will be three metal detector lines: male-only, female-only, and egalitarian. In addition, Sifrei Torah, siddurim, chumashim, and other ritual items for prayer will be available, paid for with state funding.

Women of the Wall’s monthly Rosh Chodesh service will be moved to the new area when the expansions are completed. Until then, they will continue to meet in the existing women’s section.

The Egalitarian Kotel will be governed by the Southern Wall Plaza Council, comprised of representatives from the Masorti and Reform movements, Women of the Wall, the Jewish Federations of North America, and the Israeli government. The committee will be chaired by the Chair of the Jewish Agency. The site administrator will be a government employee appointed by the Prime Minister.

The plan also mandates that the Southern Wall Plaza Council and the Western Wall Heritage Foundation hold a roundtable meeting at least five times per year to address and resolve issues that may arise.

So this is exciting news, right?

As we might expect, the Masorti and Reform movements, along with Women of the Wall, immediately released joyous press releases. But – surprise, surprise – not everyone is happy.

Rabbi Rabinowitz compared the division of the wall “among tribes” to the sinat chinam, the senseless hatred, that according to tradition, led to the destruction of the Second Temple.

On the other side, some are asking, “when did ‘separate but equal’ become the goal of any civil rights movement?” A splinter-group calling itself the “Original Women of the Wall” has pointed out that Orthodox women who do not feel comfortable in egalitarian services now have no place to pray in a women’s minyan.

Time will tell how this plays out.

Last Sunday during religious school tefilah, we spoke to the students about the exciting news. I quickly realized that most of the kids there had absolutely no idea what we were talking about.

Some of them knew what the kotel was. Almost none of them knew what a mechitzah was. A mechitzah is the separation barrier between men and women in an Orthodox synagogue. So I had to start from the beginning.

You see, here in liberal, egalitarian Northern California, most of us never experience explicit segregation, whether by gender, religion, or ethnicity. I am not talking about more subtle forms of segregation, which certainly exist. But we do not typically encounter physical mechitzah‘s in our daily lives. Quite the opposite. We emphasize diversity, multiculturalism, and tolerance. We give our girls and boys the same education, and we deliberately try to instill the belief that gender should neither be a hindrance nor an advantage to them in their lives. Egalitarianism is all they have known.

Which means that we are not doing a very good job of preparing them for the real world, or even the Jewish world.

I explained to the religious school kids what a mechitzah was, including that there are many different kinds. I pointed to the balcony in our sanctuary, and told them that in some synagogues, a balcony like that would be the women’s section and that women would not be able to lead any parts of the service.

Then I shared with them about my experiences growing up attending an Orthodox Jewish day school. When I was in middle school, we had daily tefilah in the auditorium. There was a mechitzah down the middle comprised of portable room dividers. Of course, only the boys could lead services. As a boy, it did not strike me as a big deal. It was simply how things were.

I later found out from one of my friends from the other side of the mechitzah that whenever the girls started praying too loudly, the teachers shushed them – female teachers, mind you. My friend, who attended the same egalitarian, Conservative synagogue that I did, was really upset about it. After all, like me, she was accustomed to going up to the bimah on a regular basis. I felt a little guilty myself, now that I knew that I was being given opportunities that were being denied to my classmates because of their gender.

As you can imagine, most of our religious school kids were shocked to hear this. It was so foreign to everything that they have learned and experienced.

It is important for us to prepare them for the wider Jewish world. Our goal is to raise kids into committed, knowledgeable Jewish adults. If we succeed, then they will find themselves in other synagogues from time to time in their journeys through life. When they encounter other ways of being Jewish, will they appreciate the differences or will they negatively judge the unfamiliar? That depends on how we teach them.

Where do we draw the line between embracing pluralism and diversity and holding on to our principled positions? How do we teach it to our kids?

The message that I tried to convey to our Religious School students is to, when we are in our own home and community, fully embrace our values. We are committed to Jewish tradition and history, but we understand that times change and our understanding of what the Torah asks of us changes. It has always been this way.

At the same time, we must understand that the Jewish world is diverse. There are many communities which, like ours, take Judaism seriously, but practice it differently. When we are guests in those communities, it is important to be respectful. I don’t have to like it, but just because I do not like it does not mean it is not an authentic expression of Judaism. Ours has never been a monolithic tradition.

Which is why things get complicated in the public arena. Sometimes, having things my way means that those who disagree with me cannot have it their way.

Charedim represent a minority of the Jewish world, but a majority of those who frequent the kotel. To what extent should their needs for segregated prayer spaces and suppression of women’s voices take precedence over the needs of other Jews who want access to the kotel in a way that is more egalitarian?

The answer to that question is sure to disappoint someone, as we have seen already with this most recent decision by the Israeli Cabinet. But it is a question that we have got to be engaged in openly and honestly.

At the end of this morning’s Torah portion, there is an incredible moment. Moses comes down from Sinai after receiving the laws from God. He assembles the entire nation together at the base of the mountain. He repeats all of the mitzvot to them. The people respond with an unprecedented declaration of unity: vaya’an kol-ha’am kol echad. “and the people answered with a single voice and said, “All the words that the Lord has spoken we will do.'” (Ex. 24:3) All of the people are there: men and women, adults and children, old and young – nobody is left out. There are no mechitzah‘s. And they speak in unison, although to be precise, the verb is singular. The people speaks in a single voice.

At this moment, in accepting the Torah, the Jewish people exists as a singularity. Since then, groups of Jews in different times and places have found different ways of living up to that commitment. Even though practice has varied considerably, we all look back to this foundational moment of embracing the Torah with a single voice.

I would hope that we, the diverse Jewish people, can find more opportunities to discover shared values and aspirations. I pray that our holy places, especially the Kotel, will one day cease being an object of contention that divides us and serve rather as a symbol that brings us together as a single people from the four corners of the earth.

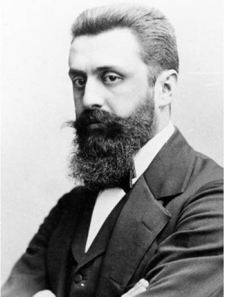

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.