Something that I have tried to emphasize about the Book of Genesis is the moral ambivalence of its narrator. The text rarely passes judgment on its characters. Instead, it allows them to speak for themselves, without judgment. It is one of things I love about the book.

In the various troubled relationships between siblings, parents, neighbors, enemies, and even God, the text never tells us that one of them is right and the other wrong. Ishmael and Isaac, Esau and Jacob, Joseph and his brothers – the Torah lets their actions, their words, sometimes even their inner thoughts, speak for themselves.

We bring our own predilections to the text. It is important for us, as readers, to recognize our biases. We might have a tendency to favor the underdog, to always suspect the motives of the winner, or to favor the “heroes” and whitewash their mistakes.

Traditional religious biases lead many, but not all, of our commentaries to see Jacob, for example, as pious, morally justified, and honorable. On the other hand, biases of moral indignancy lead many contemporary readers to view Jacob as a lying, cheating manipulator. But the Book of Genesis does not present him either way. It is non-judgmental. He is a flawed protagonist certainly, but a hero nonetheless. That is what makes him so human, and makes our emotional reactions to him so strong. After all, he is the father of the Jewish people.

When we have strong emotional responses to biblical characters, it should prompt us to ask ourselves why we are reacting with such intensity. The stories can be seen as a kind of literary Rorschach Test, with our reactions telling us who we are and what concerns us.

In Parashat Vayigash, Jacob our Patriarch nears the end of his life. It offers a natural opportunity to conduct a grand analysis of his life. But rather than projecting ourselves into the text, this morning let us instead allow Jacob to speak in his own words. First, let’s set the scene.

Upon revealing himself to his brothers, Joseph invites them to bring the entire family down to Egypt. After many years apart, Jacob is finally reunited with his beloved son. Joseph helps the family get settled in the land of Goshen, where they will be able to pasture their flocks in peace and prosperity. Finally, Joseph arranges to have his father meet his boss.

Imagine, for a moment, what that meeting must have been like for each of them.

Pharaoh is about to meet the father of his Viceroy Joseph. I bet Pharaoh felt a certain degree of awe towards Joseph – a foreigner, brought out from prison. He has strange and powerful abilities to interpret dreams which are supplied by his equally strange God. Not only that, but he has single-handedly predicted and solved a famine that would have otherwise been catastrophic and could possibly have led to Pharaoh’s ouster. And now, Pharaoh is about to meet this guy’s father. When Jacob walks into the room, Pharaoh is immediately struck by the extreme age of the old man. He has never seen someone so old. What unnatural powers must he have?!

How about from Jacob’s perspective? He is about to meet the most powerful man in the world. This man has taken in his favorite son, long-presumed dead, and made him his second in command. Jacob could be feeling grateful, or perhaps he is jealous and resentful. Has Pharaoh replaced Jacob as Joseph’s father?

Now listen to the Torah’s description of their meeting.

And Joseph brought Jacob his father and stood him before Pharaoh, and Jacob blessed Pharaoh. And Pharaoh said to Jacob, “How many are the days of the years of your life?” And Jacob said to Pharaoh, “The days of the years of my sojournings are a hundred and thirty years. Few and evil have been the days of the years of my life, and they have not attained the days of the years of my fathers in their days of sojournings.” And Jacob blessed Pharaoh and went out from Pharaoh’s presence. (Genesis 47:7-10, translation by Robert Alter)

Jacob’s blessings of Pharaoh bookend a single question and answer exchange between these two figures. And it is a strange exchange which prompts many subsequent questions.

First of all, what are these “blessings” which Jacob bestows upon Pharaoh?

Rashi, along with several other commentators, suggests that in this context, the word va-y’varekh does not mean “then he blessed”, but rather “then he greeted” – she-ilat shalom, “inquiring into well-being,” as he calls it.

Ramban disagrees, claiming that it is improper to greet a king. Rather, he argues, it is customary for elderly and pious people to bless kings with wealth, property, glory, and the advancement of their reign. Upon departing from Pharaoh’s presence, Jacob blesses him as well. According to the Midrash, Jacob prays that “the Nile should rise up to his feet.” (Tanhuma, Naso 26)

The central part of their interaction is comprised of Pharaoh’s question and Jacob’s answer. “How many are the days of the years of your life?” Pharaoh asks.

According to Ramban, Pharaoh is immediately struck by Jacob’s appearance. He has never seen someone so old in all the years of his rule. Nahum Sarna explains that the ideal lifespan in Egypt at that time was 110 years, which turns out to be the length of Joseph’s life. Jacob appears much older, prompting Pharaoh’s question. It sounds almost like he is blurting it out. He can’t help himself. Consider, is this the question that we would expect Pharaoh to ask of the man who raised his Viceroy, the person responsible for saving Egypt? How old are you?!

Jacob’s response is equally surprising. “The days of the years of my sojournings are a hundred and thirty years. Few and evil have been the days of the years of my life, and they have not attained the days of the years of my fathers in their days of sojournings.”

Jacob’s response sounds so bitter and angry. He is filled with regret and disappointment.

The commentator Ramban throws his hands up in bewilderment: “I do not understand the meaning of our forefather’s words,” he admits. “For what reason would he complain to the king?”

Jacob compares himself to his father Isaac and grandfather Abraham. He is currently 130 years old, and already is convinced that he will not live as long as his predecessors. Radak explains that he has experienced so much suffering that it has weakened him and he can feel death creeping up. How he knows this is a mystery. He is not exactly on death’s door. After all, he does live another seventeen years.

Our commentators read Jacob’s response closely and unpack it. “Few and evil – me-at v’ra-im – have been the days of the years of my life.” Rashbam explains that Jacob appears even older than he is because of all of the suffering he has been through. It has caused him to age prematurely. (Although how someone who is 130 old could be prematurely aged is something of a mystery.) In describing himself as a sojourner, Jacob is claiming to be a stranger. Everywhere he has lived, he has been unsettled, dwelling as an alien amidst local populations. Sforno adds that Jacob claims that his father and grandfather did not have to deal with the same tzuris, troubles, that he had, which is why they lived longer.

The 13th century French commentator, Hizkuni, has a more critical take on Jacob. Essentially, he calls him ungrateful. He notes that Jacob’s final lifespan of 147 is 33 years short of Isaac’s 180. Why 33?

God notes that: “I saved you from Lavan, and Esau, and Shechem, and I restored Dinah and Joseph to you, and you [have the gall to] say ‘few and evil’ your life has been. By your life, I will take from you the number of words that you have spoken.” By this, Hizkuni means the number of words in verses 8 and 9, which constitute the verbal exchange between Pharaoh and Jacob – the former’s question and the latter’s answer.

I love Hizkuni’s insight. Jacob is a bitter man, and God does not let him off the hook. Looking back on his life, Jacob sees only disappointment and regret. He is blind to the fact that he has survived all this time, that his children are all alive, and with him. He has managed to acquire everything he ever set his mind to: the birthright, the blessing, his beloved Rachel, he’s gotten Joseph back. He has become wealthy, and now finds himself in Egypt with a household numbering 70 souls, not including the wives! This is a man who has been supremely blessed in life.

But when he looks in the mirror, what does he see? Struggle, going all the way back to his uterine striving with his brother Esau. His success at acquiring the birthright and blessing has been accompanied by fear of retribution and probably guilt. He gets his beloved Rachel, but at the “expense” of being first tricked into marrying Leah. He builds a large household, but one that has been mired in scheming, distrust, and discord. He receives a new name, Israel, but walks away with a limp to serve as a reminder for the rest of his life. He has twelve sons and one daughter, but has to grieve for 22 years over the presumed death of his favorite, knowing that his playing favorites makes him at least partially responsible.

While everything, in the end, has worked out to Jacob’s advantage, the road, from Jacob’s perspective, has been torturous, and that is all that he is able to see.

What do we see when we look at Jacob? Each of us has to answer that on our own. But I would urge us to remember that we are our own worst – and potentially best – critics. And what we see in Jacob probably ought to tell us something about ourselves.

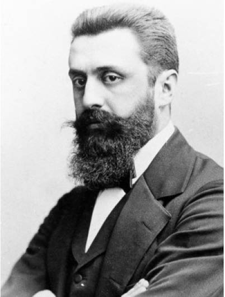

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.

Theodor Herzl, who would later become the father of modern Zioinism, is a secular Jewish journalist from Austria. He is putting the finishing touches on his book Der Judenstaat – The Jewish State, earning him some notoriety. He has developed a relationship with the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Gudemann, who has become a good friend and advisor. One day Rabbi Gudemann comes to Herzl’s home to discuss the forthcoming publication. Rabbi Gudemann is shocked by what he finds. Later that day, Herzl writes about it in his journal. It is December 24, 1895.